- Home

- Victoria Bond

Zora and Me Page 3

Zora and Me Read online

Page 3

He adjusted his red guitar strap and headed for the road, strumming the same song and humming, his sweet moan like a trail of tears behind him.

It was getting on dinner, and we walked Teddy as far as his “path” before heading to the Hurston home, where I ate on Monday, Thursday, and Friday evenings. Zora had only to hit the first step on the porch of their eight-room house for her mama to know it was her. She often said that, of all of her children, Zora’s footsteps sounded most like her own. Not many folks pay close attention to what their own footsteps sound like, but Lucy Hurston did.

“That Carrie you got with you?” she called. “Better be!”

“Yes, Mama,” Zora answered, opening the front door. “We just been at the Loving Pine.”

I used to eat at home with my mama and daddy every night, just the three of us, except for when my daddy was working out of town. As far back as I can remember, my mama was always out of the house by the time I woke up, gone to work in the laundry at the big Park House hotel in Lake Maitland. A month after my daddy left for Orlando, she picked up a second shift three nights a week. Used to be I had breakfast with my daddy, lunch at school, and supper with my mama and daddy both, but with him gone and her working so much, it was awfully lonely eating. I guess Zora told her mama about it, because the next thing I knew there was Mrs. Hurston visiting my mama, asking if she could spare me the nights she worked late, on account of Mrs. Hurston had so much housework, what with the new baby, and she could really use an extra set of hands.

As we walked into the kitchen, we saw Billie Bronson standing by the sink with Mrs. Hurston. Billie was maybe only twice our age, but she seemed very grown to me — not old so much as earnest. I supposed doing something as important as delivering babies made her very serious about life.

“Hello, Miss Billie,” Zora and I said in unison.

“Hey, you two.” She had a soft voice, not crackly like Old Lady Bronson’s. Her hands were deep in her apron pockets, but her fingers couldn’t keep still. Billie gave Mrs. Hurston a worried glance.

Billie said, “When I left my granny after lunch, she was going to fish some supper and look for some eucalyptus to boil with lavender to help soft up Mrs. Calhoun’s back some. Y’all know Mrs. Calhoun’s expecting a baby next month?” We nodded, though it was still hard for us to imagine our teacher having a life outside of school. “Well, my granny should have been home hours ago, and I been looking everywhere!”

I had never heard Old Lady Bronson referred to as anyone’s grandma before, and the title coupled with the affection in Miss Billie’s voice startled me. Realizing that Miss Billie loved Old Lady Bronson made the woman more human to me, even vulnerable. Mrs. Hurston put a reassuring hand on Billie’s shoulder and asked us, “Y’all seen Old Lady Bronson around today?”

“We seen her!” Our heads were nodding like leaves in a storm. “We seen her!”

Miss Billie’s eyes jumped. “Where? Where did you see her?”

“Over by Blue Sink, fishing!” Zora said. “We were gonna go swimming, but she shooed us away.”

“How long ago?”

The time between school letting out and us coming in to help make dinner always seemed to us like most of our waking hours, even though it couldn’t have been more than three or four at the most.

“Um, two hours?” It was as good a guess as any.

The crease in Miss Billie’s brow came back as she started for the door.

Zora grabbed my hand, and we headed out after Miss Billie.

“Mama,” Zora called, “we’ll walk with Miss Billie to the Blue Sink and come right back.”

We caught up with Miss Billie and fast-walked in silence. I couldn’t stop thinking about Mr. Pendir with a gator head instead of his own.

Right before we turned off the road, we saw Mr. Calhoun striding toward us on his way home from the schoolhouse.

“Mr. Calhoun,” Miss Billie called, “can you help us look for my grandma?”

Zora sprinted up to Mr. Calhoun. “Old Lady Bronson was late coming home after getting your wife her salve,” she blurted out to catch him up. Mr. Calhoun didn’t ask any questions, just fell into a quick pace beside us.

There was an eerie stillness at the pond.

“Granny,” Miss Billie called out. “Granny, you here?” Her call was met with silence. Mr. Calhoun wiped his forehead with a handkerchief and walked around the west side of the sink. Zora cocked her head, like a forest animal listening for breaking twigs, then darted to the red cliff below where we’d spied the old lady after school. I followed close behind. “Miss Billie, Mr. Calhoun! She’s here!” I called. Miss Billie and Mr. Calhoun sprinted over to us. Just below us and below the ledge, sprawled on the rocks, was Old Lady Bronson. A deep purple bruise ringed her right eye and she moaned softly; her eyes were closed. Her fishing rod was floating in the shallow water beside her. I couldn’t imagine how she fell from the perch where we’d left her fishing.

Then Miss Billie climbed down the cliff to the rocks and gently cradled her grandmother’s head in her lap.

“Oh, Granny!” she whispered. “You OK?”

Old Lady Bronson opened her eyes for just a second and laughed weakly. “You ain’t rid of me yet, Billie Marie Bronson!” And with that she fell faint again.

Mr. Calhoun picked Old Lady Bronson up in his strong and steady arms and carried her up out of the sink. Thin and small as she seemed with her eyes closed, the old lady still had a formidable presence.

Mr. Calhoun smiled at us. “Don’t you girls worry. I think she’s gonna be OK.” Then he and Billie headed off to Old Lady Bronson’s house.

Just as they disappeared from the clearing into the trees, we heard a tiny noise that made us both look up. In the twilight we could see the outline of Mr. Pendir’s little house. In the doorway, against a light from inside, we saw the unmistakable silhouette of Mr. Pendir leaning against the jamb. His head was as human as mine, but the sight of him watching us sparked my imagination something powerful. Suddenly Zora’s story didn’t seem so far-fetched at all. Suddenly I believed he might change shape right there in front of us. I heard a booming beat and then realized it was coming from inside me, as if someone had replaced my eardrums with kettledrums.

Zora took my hand. We backed slowly to the tree line, then tore off running to her house.

I had never run so fast. When we stopped to catch our breath, we were halfway to Zora’s house and still clutching hands. Zora put her arm around my shoulder, and we heaved air until we could talk.

“You believe me now, don’t you?”

I nodded.

“I saw it. That night at the Blue Sink, I saw Mr. Pendir with a gator snout plain as I see you right now. It can’t be no accident that Old Lady Bronson — a woman who’s never been sick a day in her life — fainted and fell, and Mr. Pendir only a few hundred yards away!”

Zora had stumbled onto something. I couldn’t say what it was, but I felt it squirming in my belly.

Back at Zora’s house, Mrs. Hurston was busy fixing supper. She was relieved to hear how we’d found Old Lady Bronson. We never said a word about Mr. Pendir, but me and Zora swapped looks all through the meal and dishes.

After Mrs. Hurston had bathed baby Everett and swaddled him tight, she came out on the porch holding him and found us there.

“Why you two out here not even talking? You have a fight?”

“No’m.”

“Well, then —”

In the warming presence of her mother, Zora let loose some of her fears.

“Mama, what do you suppose happened to Old Lady Bronson?”

Mrs. Hurston raised an eyebrow. “Didn’t you say she fell?”

Zora shook her head. “No’m. We found her on the rocks under that ledge, but when we left her this afternoon, she sat as firmly as a potted plant. I just don’t see how she could have slipped.”

“What are you saying, child?”

“Do you think something pushed her?” Zora’s voice trem

bled, and I saw her mother’s whole body change to her.

“I reckon not. She’s a tough bird — besides, there’s not a soul in Eatonville would dare to harm a hair on her head!”

“Oh, Mama —” Zora stopped herself for the shortest instant, then she looked her mother square in the eye. “You know about Ghost?”

Mrs. Hurston made a face like Zora had just spoken to her in Seminole. “Say what, now? What ghost is this?”

“Ghost the gator, Mama — the one that killed poor Sonny Wrapped and then disappeared. Just disappeared!”

“Oh, that Ghost.” Mrs. Hurston sat down between us on the porch step and pulled Zora to her. “That was a terrible thing. Poor foolish boy.” She shook her head.

“But Mama, how could Ghost just up and disappear, big as he is? He’s the size of three of Daddy laid end to end, yet nobody can find him! It don’t make sense unless . . .”

Mrs. Hurston’s eyes hooded. “Unless . . . ?”

Zora shifted, unsure how far she could go. “Well, what if Ghost could turn into a man? Or a man into Ghost? Then nobody would know. . . .”

Mrs. Hurston turned to me. “Carrie, you think men and gators turning into each other, too?”

I looked at my friend, who was nestled against her mama’s shoulder, and shrugged. I don’t know what kind of face I had on, but I guess it was the kind that made Mrs. Hurston pull me in under her other arm, while her knees kept baby Everett rocking gently in her lap.

“Listen up, both y’all. I never seen a gator turned man, or a man turned gator, or any such thing, in my whole life. I never even heard of one till now, but I’ll tell you what: gators is bad enough, and if you ever see one, either of you, you go straight up the first tree you can find, hear? Don’t never think you can outrun a gator, but you can sure outclimb one!” She pulled us in tight. “Honestly, you girls!” She chuckled, and it was hard for me not to smile, too.

But Zora stayed serious. “You know Mr. Pendir, Mama?”

The baby started fussing, and Mrs. Hurston picked him up to cradle. “I know him to say hello. Your father says he’s a fine carpenter but works too slow. He’s not the friendliest squirrel in the nest, but he does his work and minds his business.”

When the baby settled, Mrs. Hurston cocked her head. “Why? What about Mr. Pendir?”

Zora looked off at the moon. “Oh, no reason. Just wondering.” But she kept frowning.

“What’s the matter, baby?” Mrs. Hurston asked. “You still fretting about gators?”

“No, Mama. I just got to thinking of Miss Billie and Old Lady Bronson. Will you promise never to go to the Blue Sink by yourself?”

Mrs. Hurston smiled. “I’m gonna tell you something, Miss Zora Neale. First of all, you know I can’t swim and I don’t like fishing, so I don’t know why I would ever want to go to Blue Sink. Second of all, when is the last time you ever saw me alone?” She nodded toward baby Everett, who stirred in her arms as if on cue. “And finally, if I ever come up missing, it’ll be ’cause I turned on my heels with something real important to do. And if that real important thing ever came up, you know I’d be mighty obliged to take you with me.”

“You would, Mama? Really?”

“’Course I would. You the only one around this house that moves in step with me.” She glanced at Everett, who was starting to fuss himself awake again.

“Oh, Mama.” Zora smiled and wrapped her arms around her mother’s neck.

“Oh, Zora Neale.” She touched her forehead to her daughter’s. “Now, both of you come inside and get some studying done before Carrie has to go home. I’m gonna try to put Everett to bed before he thinks it’s time for another feeding.”

At that moment, Everett let out a full-on wail, and Mrs. Hurston began to dandle him like he was in a buggy on a bad road. “Oh, Lord, this baby just wake up because I went and mentioned food!”

Zora and I quizzed each other on our multiplication tables and took turns spelling the names of all forty-five states, but Zora had to keep reminding me when it was my turn. All I could think of was how I wanted to run home and hug my own mama as hard as I could.

Zora had to go to Joe Clarke’s store after school the next day to pick up some flour and sugar for her mother, so we walked Teddy home, even though it was hardly the most direct route. Zora and I always liked going to the farm.

Before they were our age, Teddy’s older brothers Jake and Micah had been pulled out of school for good, to work the farm. By the time Teddy and us were in school, the farm was thriving, and Teddy’s parents decided to give their youngest son the chance none of the rest of them had gotten. Teddy was lucky, and he knew it. I don’t know if that’s why Teddy tried so hard in school and did so well, but I never got the sense that his brothers resented his good luck. If anything, they seemed extra proud of him — but not so proud that they didn’t love to tease him.

When we got there, Jake and Micah were hoisting bales of cured tobacco leaves onto the wagon.

“Oh, nice of you to get home just in time for us to be finished with the hard work!” Micah elbowed Jake in the ribs.

“And look,” said Jake. “He’s brought his two little lady friends with him.” Jake pretended to doff a hat he wasn’t wearing. “How y’all doing today, ladies?”

“Fine,” we said, laughing despite ourselves.

Micah put his arm around Teddy’s shoulder, like a minister giving advice to a wayward boy. “Now, brother, how many times do we have to tell you that the law don’t like a man to marry two women?”

Jake looked up from pulling the straps tight on the mule’s bridle. “It ain’t fittin’!”

“That’s right,” said Micah. “It ain’t fittin’!” And as he saw Teddy’s mama come out from the farmhouse, he added, for her benefit, “Besides, one woman ought to be more than enough. Look how much trouble Daddy has with Mama — she don’t never do what he wants her to do, ’less she wanted to do it herself already!”

Zora and I tried to keep our giggles to ourselves, but we didn’t have to worry, because Jake and Micah were howling with laughter. Even Mrs. Baker was smirking a little herself.

“If y’all quit ham-bonin’ around and get going,” she said, “we might get that tobacco to Lake Maitland in time for the train. Meantime, neither of y’all has to worry about getting married until you find a girl who can get you in a harness next to that mule where you belong — and then let’s hope she can tell you apart!”

Everybody laughed at that, Micah and Jake included. It was one of the things I liked so much about Teddy’s family — they liked each other’s company. They kidded each other, but never to hurt — if the kidding didn’t amuse the one being kidded, that would mean they’d gotten it wrong, but I never saw that happen.

After Mrs. Baker sent Jake and Micah on their way, she brought Zora, Teddy, and me into the kitchen and gave us each a thick slice of bread, still warm from the oven, smeared with creamy butter made from their own cows’ milk. In the time it took us to eat, she grilled us all on what we were doing in school, what was coming up, how we were going to study, if we were going to go to high school, like Teddy was, and so on. It was nice; it reminded us that school had a purpose beyond the day-to-day, even if we didn’t know yet where it would take us. And when we were done, she sent us on our way —“So you can do your chores, and Teddy can do his, and y’all still have time to do your studying after supper.”

We all grinned at that. Zora loved to read so much, it hardly felt like studying to her. Unlike me and Teddy, who had to work real hard to stay at the top of the class with her.

My chore for the afternoon was accompanying Zora to Joe Clarke’s. Mrs. Hurston might have sent a list with Zora, but Zora was interested in too many other things to be sure to get every item on it, and that’s where I came in. I did all the pulling down from shelves, while Zora poked her ears and dipped her mind into grown folks’ business — then shared everything she learned with me.

Besides groceries and general ite

ms, Joe Clarke’s store had more than its share of tall tales and greasy talk. The aisles might have been lined with household goods, but the air was full of the kind of ideas and words respectable ladies wouldn’t dare let in their houses — not in the light of day, anyway. So Zora sucked all that adult life right up, smiling, giggling, and listening hard the whole time. I couldn’t help but give her sideways looks. Tall talk wasn’t for me. But I knew it was part of why Eatonville thrived. We lived in a community without strangers. And the men’s stories always felt like the next installment of a good serial.

The usual group of menfolk was on the porch when we came skipping up the walk, and they talked loud as usual, whooping and hollering in a major key. Joe Clarke stood against a post looking right as rain. His marshal badge gleamed in the sunlight, and his pistol sat on his hip.

“Why, hello, Carrie,” Mr. Clarke said. “And hello, Zora.”

We helloed him back, somewhere between polite and shy. Joe Clarke was a big man, but it wasn’t his bigness that made us a little shy. Zora’s father was just as tall. But I always believed that Joe Clarke was not only the strongest and bravest man in town, but the smartest; after my father, he was also the gentlest and the kindest.

“It’s been heard all around town this day that you two are mighty deserving children, Miss Zora Neale Hurston and Miss Carrie Brown,” Mr. Clarke said. “Mighty deserving.” He poked out his already protruding belly, and he snapped his red suspenders. The gold chain of his pocket watch swayed on the hip opposite his pistol.

“Mighty deserving? What for? We didn’t win any spelling bee.” Zora smiled. “Not yet, anyway.” She gave me a wink. She prided herself on knowing more words than anybody in the school — teachers possibly included — and knowing how to spell them to boot, but she never talked fancy without a good reason.

“Girls, y’all been pegged for doing something a whole lot more important than spelling some words out. If it wasn’t for you two, Old Lady Bronson might still be lying where she fell down at Blue Sink.”

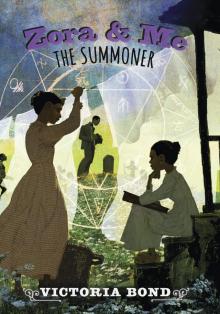

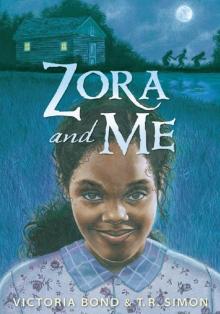

Zora and Me: The Summoner

Zora and Me: The Summoner Zora and Me

Zora and Me