- Home

- Victoria Bond

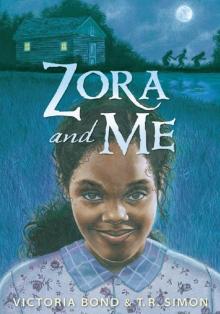

Zora and Me

Zora and Me Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either

products of the authors’ imagination or, if real, are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2010 by Victoria Bond and T. R. Simon

Cover illustration copyright © 2010 by A. G. Ford

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted,

or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means,

graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping,

and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher.

First electronic edition 2010

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Bond, Victoria, date.

Zora and me / by Victoria Bond and T. R. Simon.

p. cm.

Summary: A fictionalized account of Zora Neale Hurston’s childhood

with her best friend, Carrie, in Eatonville, Florida, as they learn about life,

death, and the differences between truth, lies, and pretending. Includes

an annotated bibliography of the works of Zora Neale Hurston, a short

biography of the author, and a time line of important events in her life.

Includes bibliographical references

ISBN 978-0-7636-4300-3 (hardcover)

1. Hurston, Zora Neale — Childhood and youth — Juvenile fiction.

[1. Hurston, Zora Neale — Childhood and youth — Fiction.

2. Coming of age — Fiction. 3. Race relations — Fiction.

4. African Americans — Fiction. 5. Eatonville (Fla.) — History —

20th century — Fiction.] I. Simon, T. R. (Tanya R.) II. Title.

PZ7.B63693Zo 2010

[Fic] — dc22 2009047410

ISBN 978-0-7636-5213-5 (electronic)

Candlewick Press

99 Dover Street

Somerville, Massachusetts 02144

visit us at www.candlewick.com

It’s funny how you can be in a story but not realize until the end that you were in one. Zora and I entered our story one Saturday two weeks before the start of fourth grade.

That Saturday, while our mamas were shopping, Zora and I were sitting under the big sweet gum tree across the road from Joe Clarke’s storefront making sure we were in earshot of the chorus of men that perched on his porch. We sat under the tree, digging our feet into the rich dark soil, inviting worms to tickle us between the toes. We pretended to be talking and playing with the spiky monkey balls that had fallen from the sweet gum branches, but we were really listening to the menfolk’s stories and salty comments and filing them away to talk about later on. That’s when Sonny Wrapped strolled up in his Sunday suit, strutting like he owned the town and not just a pair of new pointy shoes, and calling for folks to come watch him whup a gator.

Sonny was a young welder from Sanford who had come to Eatonville to court Maisie Allard. For three weekends straight, he’d been wooing her with sweet talk and wildflowers. When he wasn’t with her, he was shooting his mouth off about how tough he was. That particular day, Sonny had managed to track down the king of the gators, the biggest and oldest one in Lake Maitland, Sanford, or Eatonville. The gator’s name was Ghost, and for good reason. One minute he was sunning on a mud bank or floating in the pond, his back exposed like a twenty-foot-long banquet of rocks; the next minute he’d have disappeared, and the pond would be as still as a wall.

Anyway, Sonny got a couple dozen men to walk the short distance to Lake Hungerfort to watch him wrestle the gator. Zora’s father, her eldest brother, Bob, and Joe Clarke were among them. Nobody was thinking about the two of us, but we still had sense enough to lag behind and make ourselves invisible. Everyone stood a good ways back from the lake — close enough to see but far enough to have time to scoot up a tree if Sonny lost control.

Ghost lay still as death, but as Sonny approached, his eyes were like two slow-moving marbles. Before Sonny could jump Ghost from behind, the old gator swung his tail around and knocked Sonny off his feet.

To this day, I can still see Joe Clarke running toward Sonny, yelling, “Roll! Roll!” If Sonny could tumble out of the reach of Ghost’s jaws, he might have a chance.

But Sonny was too stunned to get his mind around Ghost’s cunning. He gaped, wide-eyed and mute, as the gator clamped down on his arm and dragged him into the water.

People began to scream. I think I remember screaming myself. One thing I remember for sure is Zora, just standing and watching without a sound, tears streaming down her face.

Joe Clarke is a big man, but he hesitated for a second — a grown man paying respect to his fear — before diving into the water. Two other brave men — Mr. Hurston and Bertram Edges, the blacksmith — dove in a moment later.

It took the three of them to drag Sonny back on dry ground. I’ll never know how. They were bruised like prizefighters. But they were better off than Sonny, whose arm had been mangled past all recognition.

Back in our homes, we chewed on silence and thought about Dr. Pritchard, awake all night trying to patch up Sonny and make him right.

The next morning, Joe Clarke rode to all the churches in his capacity as town marshal and gave the pastors the news: Sonny didn’t make it.

For two weeks after that, you would see pairs of grim men with shotguns scouring the ponds for a sign of Ghost, but they found nothing.

In the days that followed, Zora’s father said it “wasn’t fitting” to talk about what had happened to Sonny in front of women and children. Even Joe Clarke, who loved a story better than almost anyone, refused to talk about Sonny and Ghost.

Sometimes when I think back on that steamy afternoon, I can see my own father emerging soaking wet from Lake Hungerfort, Sonny’s broken body in his arms. But that was impossible, because my daddy had already been gone six months by then. And that’s another reason I remember that summer so clear: it was the summer my mama gave up believing my daddy would come home. She had cried just about all a person can cry.

As for Zora, while every kid in the schoolyard could talk of nothing else for days and pestered Zora and me for eyewitness reports, she quietly closed in on Sonny’s death, like an oyster on a bit of sand. A week later, she had finally turned that bit of sand into a storied pearl.

“I am not lying!” Zora shot at Stella Brazzle.

Zora and me and our friend Teddy were facing Stella Brazzle and her gang — Hennie, Joanne, and Nella. They were jealous of the attention kids showered on me and Zora for having been right at the spot when Sonny met his fate.

All four of those girls (Brazzles, as we called them among ourselves) were daughters of professional men — a doctor, a dentist, a tailor, and an undertaker. This meant more to them than it did to us; to hear them talk, you would have thought they were the duchesses and countesses and princesses of Eatonville. They carried themselves like every day was Easter. Nearly all the other girls would have liked to be them, and the older boys were always buzzing around them. And the more it happened, the more the Brazzles were the focus of every eye, the more they believed that they should be the focus of every eye.

“You are too lying,” Stella snapped. “You the lyingest girl in town! You so lying, even when you tell the truth, it comes out a lie!”

“He turned into a half gator,” Zora insisted. “And I saw it — I was there!”

Recess had just started, and our whole class was gathered in a tight half circle before Zora. Stella hated sharing the spotlight with anyone, but especially with Zora.

Stella Brazzle crossed her arms and smirked. “Where was this, Zora? Top of a magic bean-stalk?”

Everyone laughed except for Teddy and me. We exchanged a look and then looked pr

otectively at Zora. She didn’t notice us. Her eyes were focused on her audience.

“I’m gone tell y’all just how it happened from the very beginning,” Zora said.

“Don’t nobody wanna hear your ol’ lies,” Stella Brazzle barked. “Ain’t that right, y’all?” Not a soul moved or uttered a word — not even the Brazzles. Zora took that as a cue to begin. Everyone was eager for a story, and we all knew that nobody could tell a story better than Zora.

“I finished up my chores early last night so I could go out on the porch and catch fireflies over at the Blue Sink.” Fireflies are so thick there at night, you can just put out your arm and they’ll land on it. You don’t even have to try to catch them. “I couldn’t have been there more than ten minutes, and I’d already filled my jar, when I heard a strange whistling sound.”

You could hear us holding our breath, it was so quiet.

“What kinda whistling?” Ralph Hardiman asked, his eyebrows raised like clothespins were keeping them up.

“Strange-sounding, not like any bird or person I ever heard make,” Zora said. “But that wasn’t the worst of it. The night started getting dark and misty, and the fireflies started disappearing. Soon I couldn’t make out a thing in front of me until I got near Mr. Pendir’s house.”

“Then what happened?” Teddy and I asked in unison.

“I was surrounded by white fog, but not thick like clouds. Nuh-uh. It was stringy — like spiderwebs!” She suddenly waved her fingers at us like they were daddy longlegs, and half the circle jumped back. But nobody laughed.

“Then, as fast as it started, the spiderweb fog disappeared. I was flat on my belly in wet grass, right close up to Mr. Pendir’s porch, in the dark. I didn’t even realize I’d gotten that close. I lay there for a long minute, still as a stone, trying to steady my eyes on the glowy light inside the house.”

Half a dozen voices: “What you see?”

“The screen door swung open.” Zora paused for effect. “Out of the light stepped Mr. Pendir. But where his nose and mouth should have been, he had a long, flat gator snout!”

“A gator snout?” we all shouted — even Stella Brazzle, in spite of herself.

Zora nodded slowly. “That’s right,” she said. “Mr. Pendir looked like a gator man — man body, gator head! That’s his secret. And that’s how come can’t no gator kill him!”

One thing about gators that folks outside our parts don’t usually know is that they make loud hissing sounds. Not all the time — only when one of their young is in trouble. It’s a call to arms, and it sounds like a cross between birthing pains and dying pains. Mr. Pendir, a carpenter by trade, just like Zora’s father, was fishing in Amherst Lake one time in a tiny dugout canoe that he had built himself, when he accidentally cornered a young gator. An older gator caught sight of this and started up that horrible hissing. Mr. Pendir, no fool, knew exactly what it meant. Next thing he knew, three grown gators were in the water and swimming his way. But he didn’t panic — not the way I heard it told. He let the gators get close to his boat, then threw the bucketful of fish he’d caught right at them. It distracted them just long enough for him to jump in the water and swim like the dickens to shore. The three gators smashed his boat to pieces, but Mr. Pendir lived to tell the tale, without a scratch on his peanut-colored bald head.

If any other man in the town had survived the same experience, he would have crowed about it all over creation. Not Mr. Pendir. No one would have known about it at all if Joe Clarke hadn’t seen him carving a new canoe and asked him what happened to the old one. Everyone knew Mr. Pendir to be quiet and honest, and no one doubted the story for a minute. Still, some folks ran to the lake anyway and found the splintered pieces of the dugout canoe washed up on the shore. All of Eatonville looked at Mr. Pendir a little funny after that. So it didn’t seem so far-fetched that Mr. Pendir could actually be what Zora said he was, half gator and half man.

“Well . . . then what happened?” Stella Brazzle snapped the question, angry at herself for being curious.

“What do you think? I jumped up and ran! But the whole way home, I could hear the creaking sound of a gator opening its jaws and clapping them shut.”

Teddy blinked. “Did he follow you?” he asked, nervous, like it had just occurred to him that Mr. Pendir might be gaining on Zora and the rest of us, even now.

Zora didn’t have a chance to respond. Our teacher, Mr. Calhoun, stepped out onto the stoop of the schoolhouse and rang the bell. The spell was broken. As we all ran inside, kids shouted things like, “Aw, fibber,” “You crazy, Zora,” and, “You ain’t seen no such thing!”

“All right, don’t believe me, then,” Zora said. “But when all y’all coulda been playing kickball, you were standing around like boards listening to me. That alone is proof I’m telling the truth.” And she beamed, as proud as if they had given her a medal for bravery.

The rest of the day, I paid maybe half attention to the lessons at best. Zora had cast a long shadow over my favorite swimming hole. There’s a lot of places in and around Eatonville where you can have a swim, but Blue Sink — barely bigger around than a big house but deep enough that it never dried up — was ours. At the deepest end, an old weeping willow dipped in the water like a braided head, and we would swing out on its strong vines before letting go at just the right instant. Those moments of flying in the air before the water swallowed us in one cool gulp were pure joy, and I hated to think they were over.

But I also couldn’t stop thinking about what Zora had said. Just because something’s good listening doesn’t necessarily make it true, and Zora didn’t have any trouble telling a fib or stretching a story for fun. I could tell that Zora herself believed the story, but the question was, did I?

By the time three o’clock finally came, it was so hot that I convinced myself it was all foolishness. The three of us had been swimming at the Blue Sink since forever, and with the heat probably pressing up to one hundred degrees, I was willing to take my chances. I just had to have a dip.

Zora was walking beside me, eyeing me. “You sure?” she kept asking. “You sure you want to go to Blue Sink after what I seen last night?”

Each time she asked, I grew more determined. “I’m fixing to turn into molasses if I don’t.”

“Well,” she said, “I guess if it’s two of us, maybe he won’t try anything. . . .”

I had a pang of wishing Teddy was with us, but I didn’t say anything. Teddy always had to run home after school and do his chores on the farm before he could come out and join us.

Zora continued. “Mr. Pendir probably don’t show his gator head in the day, anyway.” Even though she’d had the wits scared out of her the night before, she didn’t want to give up the Blue Sink, either.

Spanish moss hung low over the pond like layers of gray-fringed blankets. Woodpecker and nuthatch beckoned us with snare drum rat-a-tat-tat and whee-hyah. Zora was the first to drop her books and strip down to her underclothes. I was a few beats slower, making sure to keep Mr. Pendir’s house in plain sight.

Zora ran toward the red cliff of dirt over the water but stopped short, and I almost ran into her. Someone was sitting on the ledge, fishing. When she called out, her voice crackling like hot chicken grease, I knew exactly who it was. “Y’all children run like you woke up itching to topple an old lady over!” Old Lady Bronson cried. “Just itching.”

We would be lucky to escape the afternoon without getting a spell hurled at us.

Zora’s voice was calm. “We didn’t mean any harm.”

Old Lady Bronson jerked her head to the side, flashing us her pinched profile, and her thick gray braid whipped between her shoulder blades like a long tail.

“Zora Neale Hurston,” Old Lady Bronson said, “please don’t tell me what you meant and what you didn’t mean. My first two names ain’t Old Lady for nothing. I been round here as long as there’s been a round here. Now, git! Go on. Git! I want my peace. And old ladies should have what they want.”

Zora put her hand on her hip. Old Lady Bronson might get what she wanted that afternoon, but she was also going to get something from Zora.

“If you’re not careful, Old Lady Bronson,” she warned, “Mr. Pendir is gonna get you! You might be a roots woman, but Mr. Pendir, he can take on the face of a gator! And here you are sitting all alone near his house. That ain’t safe for nobody, much less an old lady.”

“What you say, child? Pendir, a gator?” Old Lady Bronson laughed. “Girl, what folks say ’bout you is all wrong. You ain’t a liar — you just crazy as a hoot owl! The powerful ones be the little old ladies. Ain’t a soul in this town can match me for strength if the test don’t require lifting a finger.”

Everyone knew that Old Lady Bronson made spells — plenty went to her to get their broken hearts patched up or have a whammy taken off. But few got to hear her say out loud that she had conjure power. It sent the cold tingles running up my back.

But Zora wasn’t fazed a bit.

“All I’m saying is, you better watch out, if you want to keep your arms and legs,” Zora said.

“You don’t got to worry ’bout me, small fry. What you need to worry the hair off your head ’bout is getting un-crazy.” Old Lady Bronson laughed.

Once I heard a man on Joe Clarke’s porch say that Old Lady Bronson came from a long line of mean and kept a long line going. She had four daughters, all of them my mama’s age or older, and they were all mean. The youngest of them, Miss Eunice, was so mean that after she was grown and living way up by Pensacola, she came to visit Old Lady Bronson one time to borrow her mule, and took the mule but left her own little girl, Billie, who couldn’t have been more than five at the time. Old Lady Bronson had to raise Billie up herself, even though she was already an old lady. When Billie started to get grown, Old Lady Bronson taught her midwifery and, for some reason, Billie is the only Bronson woman who didn’t come out mean.

Zora rolled her eyes and turned her back on the old lady. I backed away so the old lady couldn’t cast any hoodoo dust at us while we weren’t looking.

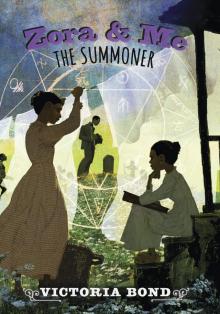

Zora and Me: The Summoner

Zora and Me: The Summoner Zora and Me

Zora and Me