- Home

- Victoria Bond

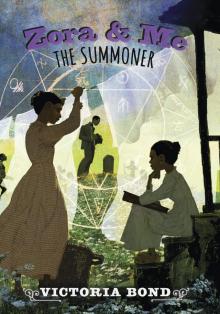

Zora and Me: The Summoner

Zora and Me: The Summoner Read online

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Epilogue

Eatonville, Florida

September 29, 1956

Granddaughter:

Every day since I was fourteen, the scar on my left hand reminds me of your grandfather, my dear Teddy. He told me that the scar would fade, and he was right — it mostly did. But when I hold my hand up in the bright noonday light, a shadow of that 1905 scar survives.

Everyone in Eatonville suffered terribly that year, including my best friend, Zora. Grief and loss afflicted us both. It chased us through a grove in the lightning and rain. At kitchen tables and on porch swings, at swamp banks and in dark cabins, loss bore down on our necks with icy blue and stinging breath. The faded scar on my hand is a testament to how Teddy and Eatonville helped me to heal in place. They were my anchors, my salve, my proof of miracles.

Grief prodded Zora to reject miracles. She insisted, instead, that earth and life on it make sense. Stories are the thing that anchored her. Eatonville itself couldn’t give her peace, but stories about Eatonville might.

She carried the story of Eatonville with her around the world. Stories protected her, healed her. And the summer of 1905 was Zora’s last in Eatonville.

And now you, her namesake, are leaving. I offer the story of our parting as a goodbye. I hope this story will be for you a harbor in the storm.

The final thing I must say is: fear no loss. Despite our efforts, loss touches us all. Stand brave, dear girl. Loss will not be your undoing. Loss cannot hold a candle to love. Love is our story.

Your grandmother,

Carrie Baker

Mama’s employers, the Brays, had gone on summer vacation to the South Carolina shore. Usually, when the Brays went away, Mama looked after Mrs. Bray’s old aunt, Miss Pitty. But in the summer of 1905, Mama had somehow convinced Mrs. Bray to take the elderly Miss Pitty along with them. It was the very first vacation she had ever been granted in a lifetime of labor. Triumphant, Mama declared her intention to keep right on working full days, but with me. Working with me, working for us, was different.

It’s almost hard to believe now that I was just thirteen when I started taking in laundry from Lake Maitland. A couple days a week, I boiled water in a zinc barrel and dropped tablecloths and sheets in with the lye soap I made. I stirred, I rinsed, I wrung. Then I hung the large white squares on the line alongside our house. On hot days, I stewed in stifling tedium. On windy days, the linens billowed like clouds and the sight gave me pride in my work.

With Mama’s help that summer, I could complete twice the loads in half the time. I was able to earn more, too, with leftover time for relaxing. Instead of unpinning sheets from the line and ironing in the early evening, I could sit beside Mama on our porch swing, cross-stitch, and watch the deepening sky coax out the first stars. That summer, Mama’s oval face glowed with health and peace. I remember feeling the only way you can after spending a perfectly sorted day doing good and honest work beside someone you love: grateful.

On one such evening, the sound of an engine and a small black cloud announced the speedy approach of a horseless carriage. We squinted into the setting sun to make out who it was.

“It’s Mr. Baker,” Mama said. I stood, overjoyed, certain that Teddy would be with him. Teddy hadn’t mentioned dropping by. No matter. Whether he appeared at my door, we met at the Loving Pine, we crossed paths in the forest where there were no paths, or we bumped into each other on Joe Clarke’s porch, where it felt like all paths led, Teddy, in my heart and in my home, was always welcome and always new. Teddy waved from the front seat, beside his father.

The horseless drew very close now. Mr. Baker parked it next to a spiky, squat palm in our yard and killed the engine. There was another surprise! Zora was riding in the back.

“Hello there,” Mr. Baker called, his silver spectacles catching the light. His friendly, routine words were one thing, his tone another. He sounded as if he were trying to keep down a roaring cough, stifle something. Teddy got out of the automobile in a hurry, but Zora still managed to beat him to the dooryard. They were both electric with some sort of news. I couldn’t tell if it was bad news, exciting news, or both.

Mama picked up on it, too, and got straight to the point. “Alan, what’s going on?”

Mr. Baker took off his hat. “A white law man came to Joe Clarke’s today,” he said cheerlessly, “a sheriff from Sanford.”

“What about?” There was dread in her voice.

“There’s a man on the run by the name of Terrace Side,” Mr. Baker said. “This white sheriff says this Mr. Side escaped from a chain gang stationed in Georgia, at the border. The authorities suspect the fugitive’s trekking all night and hiding out all day. They even suspect he’s heading to Eatonville, for refuge.”

“Why?” Mama asked. “Does he have people in Eatonville? Ain’t no one here called Side, is there?”

“No, ma’am,” Mr. Baker answered. “But that sheriff thinks Side would come here, counting on the protection of something more formidable than a single colored family: an entire colored town.” Mr. Baker paused. “You know what Joe Clarke told that white man to his face?” he asked, a small grim smile on his lips. “He said, Eatonville doesn’t harbor murderers, black or white.”

“That’s just what Mr. Clarke told him,” Teddy said, awe and respect in his voice and expression.

“So is that what this Side fellow got put away for, murder?” Mama was more businesslike than impressed.

“Yes,” Mr. Baker answered, “according to that sheriff.”

“But do we know for sure?” While I reeled, Mama’s common sense raged. “For all we know, he might have knocked over a houseplant in some rich white lady’s house. For all we know, this man may be guilty only of running for his life.”

“We don’t know,” Mr. Baker said, somber and defeated-like. “The one thing we know for sure is that the white law man says anyone who dares to abet the fugitive will be punished, severely. Search parties from Georgia will be coming through, looking for Side’s hideout. So we’ve got to get the word out to everyone, including folks in Blue Bay and Lake Catherine. Keep your door and windows locked, a lantern lit,” Mr. Baker advised. “A house with the lights on won’t look like a good hiding place to either a fugitive or a mob.” Mr. Baker looked at Teddy. “We better get on. We’ve got the ride of Paul Revere ahead of us and still got Zora here to drop home.”

An awkward silence followed.

John Hurston was on the road and had been for weeks, traveling the borders of Alabama, Georgia, and Florida on a preaching tour. Lucy Hurston had been taking to her bed on and off since he’d gone. More than ever, Zora was needed at home.

“This is all precaution,” Mr. Baker tried to reassure. “That’s all, precaution. I’m not sure that Side man is here in Eatonville. The poor man may very well be apprehended even before the search parties get her

e.” Mr. Baker shook his head. “Heaven help him if he is.”

“I’m no martyr, so I’m not going out looking for Side tonight,” said Mama, “but if Side finds his way to my house seeking refuge, it’s my Christian duty to help him.”

Teddy blinked, rocked back on his heels by my mother’s bravery. Zora got incredibly still. In admiration, I think, for Mama’s Christian virtue. My lips quivered. Mr. Baker pursed his. “Be careful,” he cautioned, “very, very careful.”

“I will,” Mama answered quietly, “by putting my faith in the Lord. Tonight, I’ll be praying for everybody in Eatonville, everybody.”

After a late supper, we set our hands, if not our minds, to sewing and needlework at our table. Mama worked on trimming the collar of a blouse with a lace wreath. I returned to my cross-stitch of a lamb beneath the crucifix. Earlier I had made such little progress on the rugged cross that I abandoned it altogether to work on the lamb’s ebony eyes. As I threaded a new needle with black thread, we were startled by howls, barks, and the trampling of feet in our dooryard.

In one fluid motion, Mama rose from her chair, grabbed me, and shoved me under the table. Staying on her hands and knees, she crawled over to the front window and crouched below it. The porch swing chain jangled and shrieked and whined. Dogs scratched wildly at the door. Fists pounded at it. The butt of a gun hammered at it. The hinges rattled. My bowels tightened.

“Open up!” a voice ripped the night. “Open up!” The dogs quieted and the swift response to an order of any kind indicated there were fewer animals than I feared, probably no more than three, but it only took one dog to maim, kill. Who were these people who had come with dogs? Why were they here?

“I live here,” Mama called, her voice steady. “This is my house.” Mama and I locked eyes. Hers instructed me to remain silent.

The butt of a gun hammered again, hard. “Fugitive search! Open up! Now!” Mama jumped up and sprang the door ajar.

Two dogs, three men. The man with the rifle stepped into our home. One of the dogs came with him. One look and I knew I couldn’t maroon my mother. I crawled out from under the table and hurried over to stand beside her.

“That’s right,” the man said, his tidewater-green eyes appraising us. The dog sniffed around our meager sitting room, put its paws on our table and our sewing, then dashed off to our bedroom. The animal was searching for the scent it had been trained to find: Terrace Side.

“Why are you here?” Mama asked.

The man went to our table and rubbed a dirty thumb over the paw print left on my cross-stitch by the dog, deepening the stain. The kitchen clock ticked slowly, loudly. “We’re looking for something. My dog Pixie will tell us if that something happens to be here.”

One of the other two men also stepped inside. A wide-brimmed hat made his neck look thick. The third kept watch on the porch with the other dog. Pixie came out of our bedroom and returned to her master’s side.

The man rubbed the dog’s fawn-colored fur affectionately. “Pixie say no one else here. Pixie say you all alone — till we got here, anyway. I can’t believe that, the two of you, much prettier than them fancy ribbons and lace. Much prettier,” he nattered on. “And you all alone.”

Tidewater Eyes reached out and laid his filthy hand on my mother’s neck. Thick Neck lifted the brim of his hat to better observe his friend’s actions.

I held my breath. Mama gritted her teeth. I feared this man’s touch was going to choke us both. “Sir”— fear and disgust stretched Mama’s lips into a grimace —“if your business here is done, please leave us be.” Then she prayed. “Please, Lord, please. Instruct these men to leave us be.”

God answered, with a solution the devil could cotton to. Out on the road, an engine snarled and a horn tooted shrilly.

Then a monstrously musical voice beckoned: “The nigger’s been caught! Come on, fellas! Come on outta there! Let’s go have us some real fun! Yahoo! Bells are a-ringing! Bells are a-ringing! The nigger’s been caught at Lake Bell! Let’s go have some real fun! At Lake Bell! Yahoo! The nigger’s been caught at Lake Bell. Bells are a-ringing!”

Two women alone in a house were a mere sideshow. The torture of Terrace Side was the main event. The man and the dog on the porch went to join the troop down on the road. Thick Neck also withdrew. Tidewater Eyes removed his hand from Mama’s neck. I quickly grabbed her wrist, in order to subdue her urge to spit in his face.

“We’ve got to go,” he said, almost as if he were apologizing. “But would you first be so kind as to answer a question for me?”

He didn’t bother to wait for Mama’s answer.

“How far is Lake Bell from here?”

Mama admitted what could not be disputed: “Not far.”

“Not far as in the next town over, or not far as in right here in your little colored part of this country?”

Mama was silent.

“Ah,” he said. “Looks like Eatonville is a winner!”

The horseless rattled to life, and Tidewater left, Pixie trotting beside him.

Hell moved on in a pack. It had less than a quarter mile to go before arriving at Lake Bell.

Mama stood limp by our table. I staggered over to close the front door and then retched. The gesture shattered the veneer of my anger. Raw pain at our vulnerability writhed beneath it. Finally, Mama and I collapsed and wept, clinging to each other as if to rafts in a flood.

We didn’t know Terrace Side, had never laid eyes on him. Yet he had delivered to us a near-catastrophe.

Near dawn, we finally slept. When we woke at midmorning, Mama and I dressed and went immediately to the Hurstons’ to check on them. Everywhere the air was smoky, putrid, gray. The mob had set a fire; that much was sure. Sadly, I prayed that if Terrace Side had died, he had done so alone, that no one from Eatonville had suffered alongside him.

The shadows of the chinaberry leaves flickered on the Hurstons’ roof. Lucy Hurston sat on the porch in the tall rocker: a papery blossom, hardly occupying a sliver of shade.

On seeing how Mrs. Hurston looked, Mama dashed up the path ahead of me. “Lucy Hurston!” Mama scolded. “You should be in bed! Why you out? Why?”

Lucy Hurston smiled weakly. “I feel better than I look, and that’s saying something at a time like this.” She slid on her cotton corded slippers and made to stand, using the arms of the chair for support. Mama went to steady her, but Lucy Hurston held her own.

“Old Lady Bronson’s lemon-and-onion syrup would do you some good,” Mama declared. “And with all those pills Doc Brazzle rolls, he sure enough must have something that will help you rest, sleep.”

Zora came out on the porch. Mrs. Hurston grabbed her daughter’s hand. “Who could sleep with what went on in this town last night?” Lucy Hurston asked. “Tell me, did you sleep?”

“Barely,” Mama answered. “We had unexpected visitors.”

Zora reached out to me tenderly, but I involuntarily flinched. The shock at what my reflex intimated caused her to throw her hand to her mouth. I had surprised even myself. Contritely, I took her hand and placed it over my heart, my way of reassuring her. The realization startled Lucy Hurston. Mama shook her head and said, “No, not that, thankfully.”

“Are you all right?” Lucy Hurston asked softly. “You really both all right?”

“Yes,” I answered.

Zora exhaled. “The mob rode past here. We heard them. That was all. That was enough.”

“Side was discovered at Lake Bell,” Mama said. “The men that came to our place went with a gang there —” And Lucy Hurston shivered with the knowledge of what the mob went there to do, how men with their guns cocked and torches alight could set foot anywhere — on our shores, our land, our doorstep — and assume ownership of all our property, including our bodies and souls.

Mama said, “Let me take you inside, Lucy. You should be lying down.” Mrs. Hurston obliged, and the two disappeared inside the house.

Ever since Lucy Hurston had returned home from Alabama, sh

e’d been bad and then worse.

Her youngest sister had birthed a baby boy two months before it was his time to come. A letter arrived detailing how the first-time mother had lost a pitcher of blood, the baby no bigger than a pine cone. Immediately, Mrs. Hurston set out for Notasulga, Alabama, by train to be with her sister and tiny nephew. Neither survived.

While Mrs. Hurston was in Alabama, John Hurston began what was to be his last preaching tour. It was Lucy Hurston who had pushed the idea of it being his last time out on the road. At first, John Hurston resisted. Lucy Hurston, however, got her husband to think bigger. “Powerful men don’t go running behind folks,” she told him. “Folks run to see powerful men. You a mighty powerful man, John. You’ve paid your dues out on the road, John. It’s time you reap the rewards here at home. It’s time you let folks come to you, where you live.”

Reverend Hurston could not quarrel with that. Once upon a time, he had been a nobody from across the creek. Now he was a respected citizen of America’s first black-run incorporated town and a man of means. Mrs. Hurston had used her husband’s own ego and self-image to get him right where she needed him: at home, in Eatonville.

“One moment, Mama looks drawn, pale,” Zora said. “The next moment, she glows some kind of sheen. Then the sweats start. They smell, so I hope that’s a sign that whatever’s ailing Mama is getting outta her system.”

“I can wash her bedding for you,” I offered. “I’ll pick it up whenever you like.”

“Thank you,” Zora said, and we went inside. In the kitchen, Zora’s sister, Sarah, was pouring tea for my mother and hers.

“By what you’re telling me,” Mrs. Hurston said, glowering, “Side was probably lynched at Lake Bell. Lynched in Eatonville. In Eatonville . . .” Mrs. Hurston believed the horror, but wanted desperately to disbelieve that it had occurred in our home, our town, on our watch. “There wasn’t anybody in this town to stop what happened to Terrace Side,” she lamented. “My husband wasn’t even here.”

The only way to find out how the rest of the town had weathered the assault was to go to Joe Clarke’s. Though the store and porch were full of folks, only one person spoke at a time and they did so very quietly.

Zora and Me: The Summoner

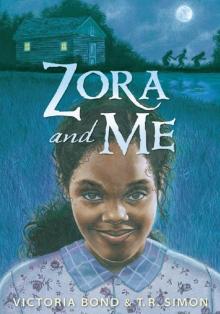

Zora and Me: The Summoner Zora and Me

Zora and Me